Florentine Spring Cake

Made by Alessandro Cipriano

Preface:

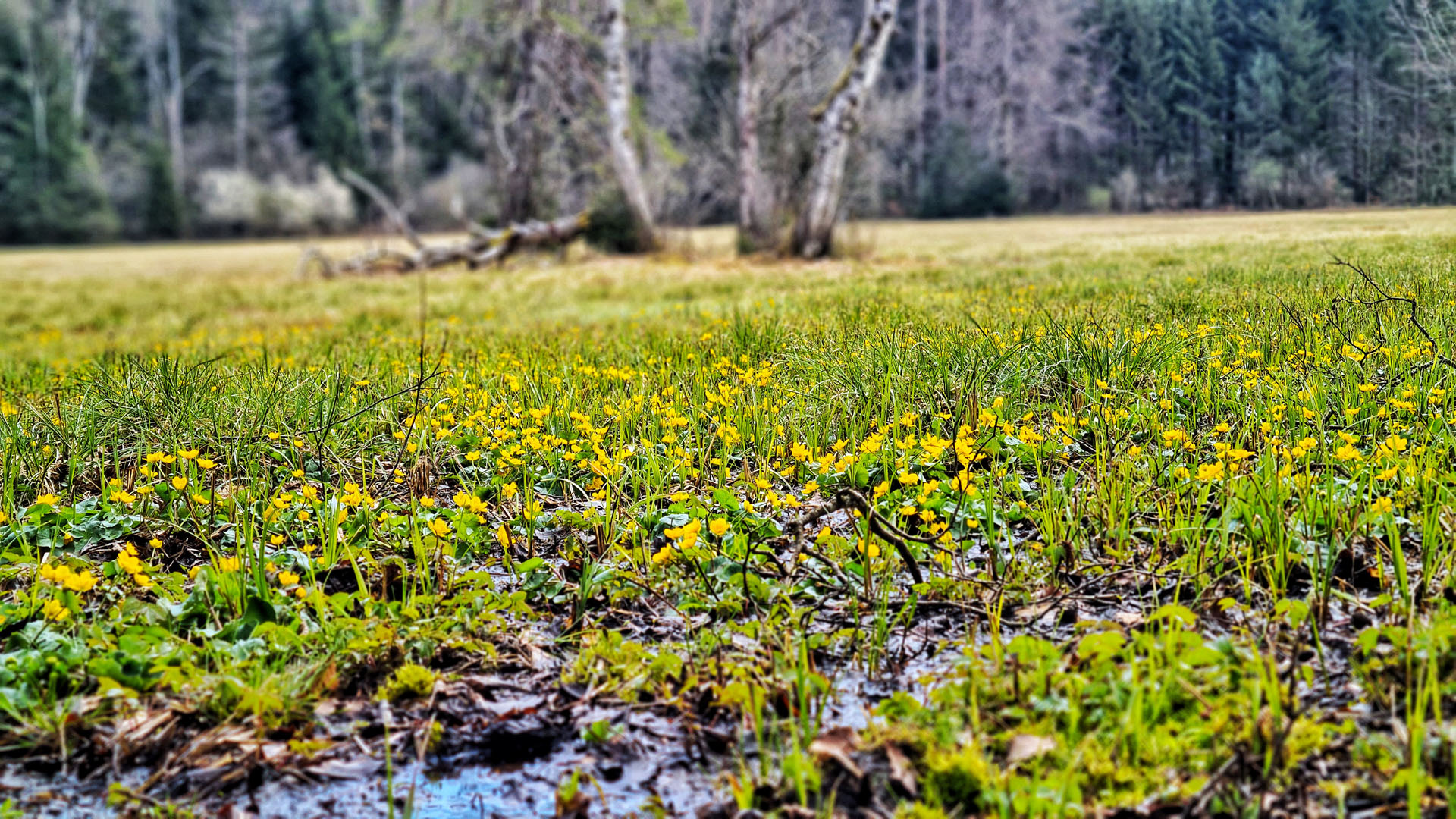

Enjoy the rich and flavourful “Florentine Spring Cake”, an old recipe from my grandma. This moist and delicious cake is infused with the warmth of vanilla and the irresistible combination of crunchy hazelnuts, sweet chocolate chips, sultanas, and dried cranberries. Each bite is a symphony of textures and flavours. Imagine taking a bite of a perfectly baked piece of cake. Your teeth penetrate the delicate crust, and an incredible taste of chocolate immediately unfolds on your tongue. It’s as if a tidal wave of delicious flavours conquers your palate. The rich, melting chocolate flavour slowly unfolds, leaving you with a feeling of bliss.

prep time: 30 MINUTES

cook time: 50-60 MINUTES

total time: 1 HOURS 20 MINUTES

cake tin (loaf tin): 30 cm

Ingredients

For the dough

- 200 g butter (soft)

- 200 g sugar

- 4 eggs

- 200 g flour

- 2 tsp baking powder

- 1.5 dl milk

- 100 g grated hazelnuts

- 100 g chocolate chips or chopped chocolate

- 100 g sultanas

- 1/2 grated lemon peel

- 100 g dried cranberries

- 1 tsp vanilla extract

- 2 tbsp rum (optional)

Glaze

- 100 g dark chocolate (e.g. crémant), in pieces

- 50 g butter, in pieces

Garnish

- 2 tbsp chopped pistachio nuts

- 1 hand sliced almonds roasted

- Icing sugar

How to do it!

Preheat the oven to 180 degrees Celsius (top and bottom heat). Grease a loaf tin (approx. 30 cm) well and dust it with a little flour, or line the cake tin with baking paper.

In a large bowl, cream the soft butter and sugar. Add the eggs and beat them in well. I use the Kitchen Aid.

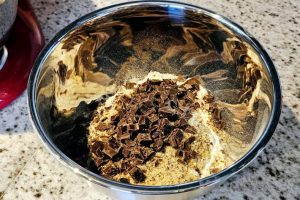

In a separate bowl, mix together the flour and baking powder. Add the hazelnuts, chocolate chips, sultanas and dried cranberries and mix well.

Gradually add the flour mixture to the butter and sugar mixture and gently stir until an even batter is formed. Gradually add the milk. Add the vanilla extract and and rum stir it in.

Pour the batter into the prepared loaf tin and smooth it out. Bake the cake for about 50-60 minutes or until golden brown, as a test take a wooden skewer inserted into the centre, if it comes out clean the cake is ready.

Once the cake has finished baking, leave it to cool in the tin. Then turn it out onto a cooling rack and let it cool completely.

Prepare chocolate icing

Melt the chocolate and butter in a thin-walled bowl in a water bath that is not too hot, stirring.

When the cake has cooled, you can spread the chocolate icing over the cake. The butter melted with the chocolate will make the icing nice and firm.

Then spread the chopped almonds and chopped pistachios on top. Sprinkle with icing sugar before serving.

Enjoy the Florentine Spring Cake as a delicious dessert or with your coffee! Enjoy your meal!